|Videos|March 18, 2021

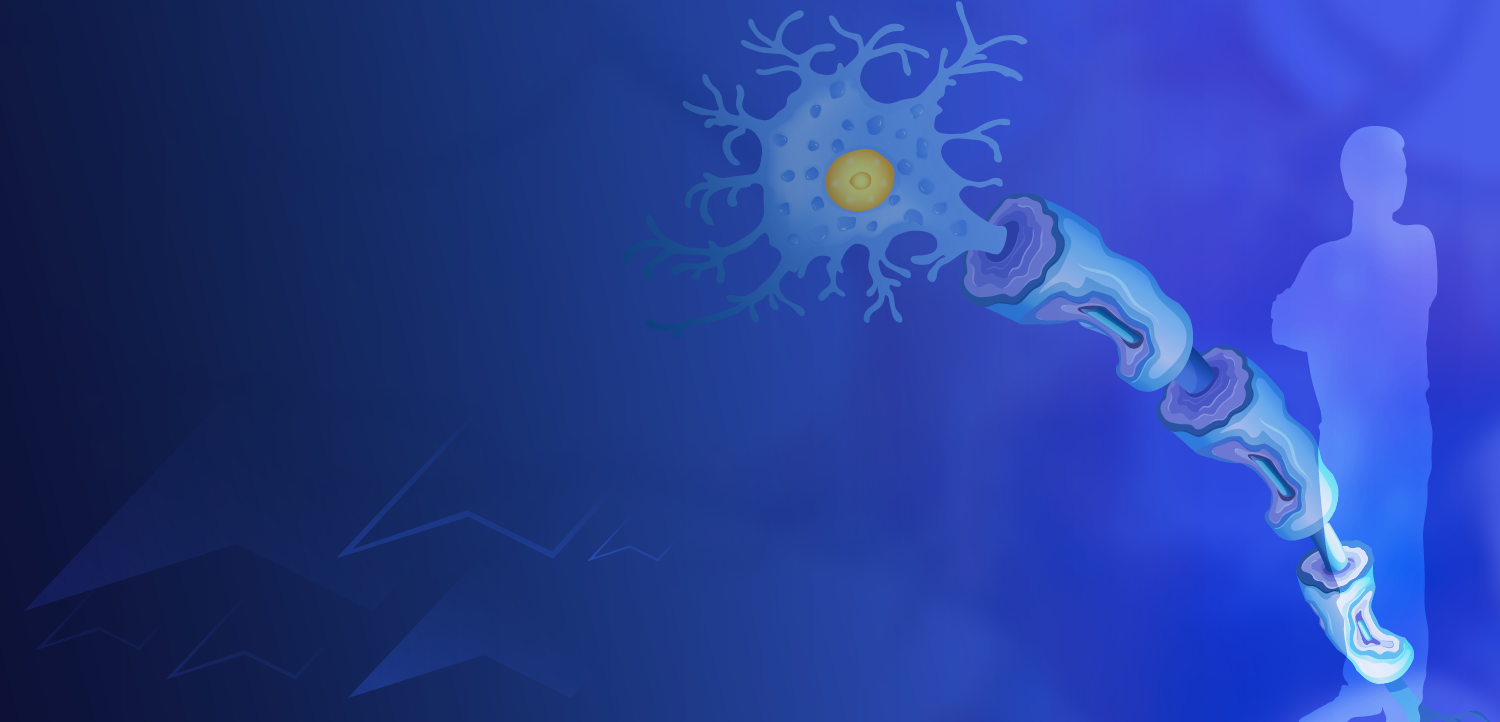

Management of Progressive Multiple Sclerosis

Experts discuss the diagnosis and treatment of progressive multiple sclerosis.

Advertisement

Newsletter

Keep your finger on the pulse of neurology—subscribe to NeurologyLive for expert interviews, new data, and breakthrough treatment updates.

Advertisement

Related Articles

Current Challenges and New Opportunities Ahead for Women in Neurology

Current Challenges and New Opportunities Ahead for Women in NeurologySeptember 15th 2025

2025 Women in Neurology Conference: Educating, Mentoring, and Networking

2025 Women in Neurology Conference: Educating, Mentoring, and NetworkingSeptember 15th 2025

Latest CME

Advertisement

Advertisement

Trending on NeurologyLive

1

Del-Zota Reverses Duchenne Disease Progression in 1-Year Trial Update

2

EMA Approves Semaglutide as First GLP-1 RA for Cardiovascular, Stroke-Related Benefits

3

Stem Cells of Secondary Progressive Multiple Sclerosis Drive Increased Proinflammatory T-Cell Activity

4

Postmortem Analysis Reveals Distinct Patterns of Aquaporin-4 in Parkinson Disease and Multiple System Atrophy

5